While I was in Tianjin presenting at the ACAMIS Conference on the Arts, I got into a conversation with my dear friend Hanna about an exhibition she was planning for early summer. The show was going to be held in an old space with new owners in the 798 Art District of Beijing—a gritty, vibrant hub for creative work. Hanna shared that she was feeling anxious about having enough pieces to fill the space. I asked her what the show was about, curious if there might be a way for me to contribute.

She told me it was going to be a tribute to her dog, Ghost. At 14, Ghost is getting older, and Hanna was starting to think about what life would be like without her. The exhibition would be a kind of homage—celebrating all the ways Ghost has inspired her as an artist and companion. That got me thinking.

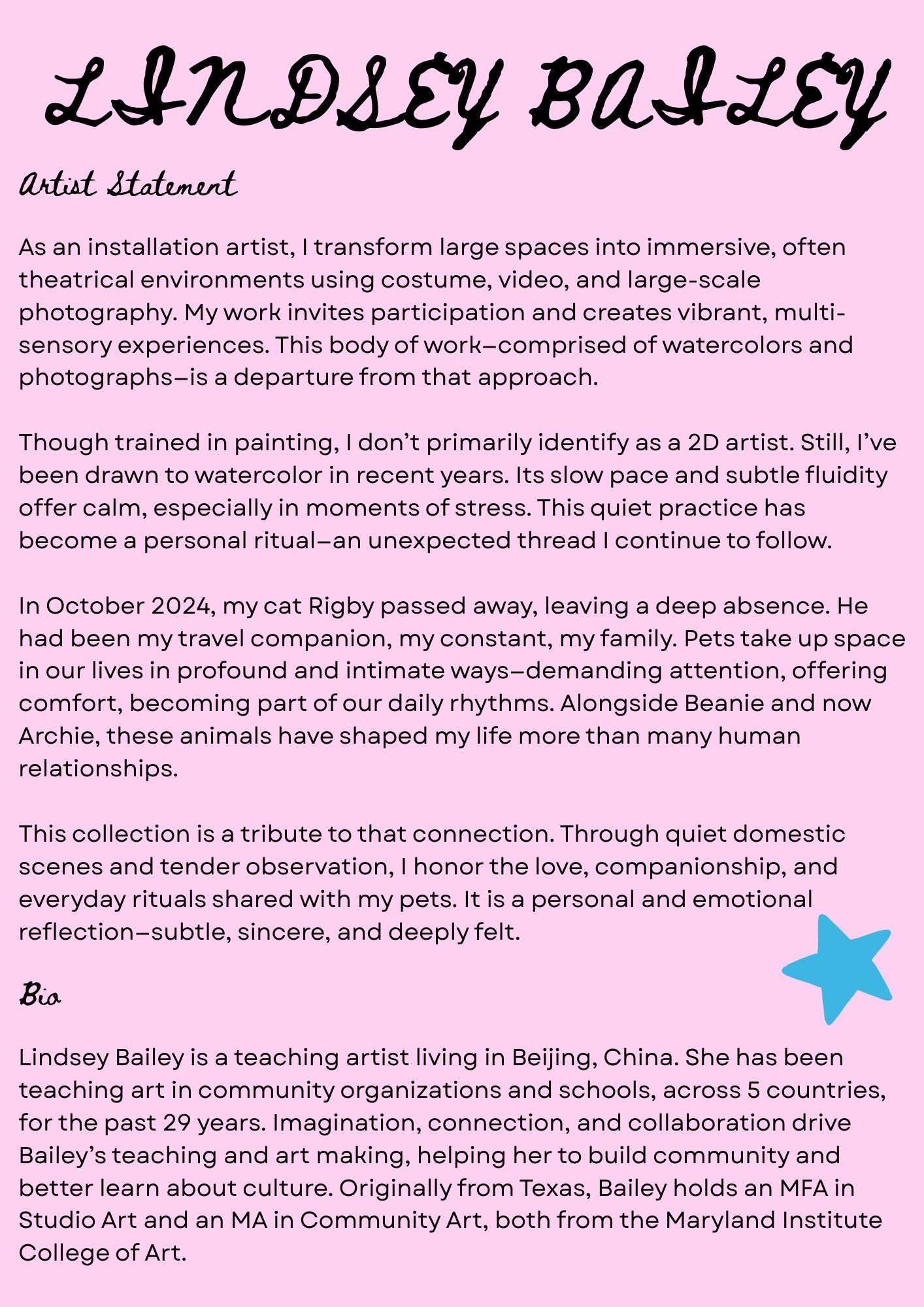

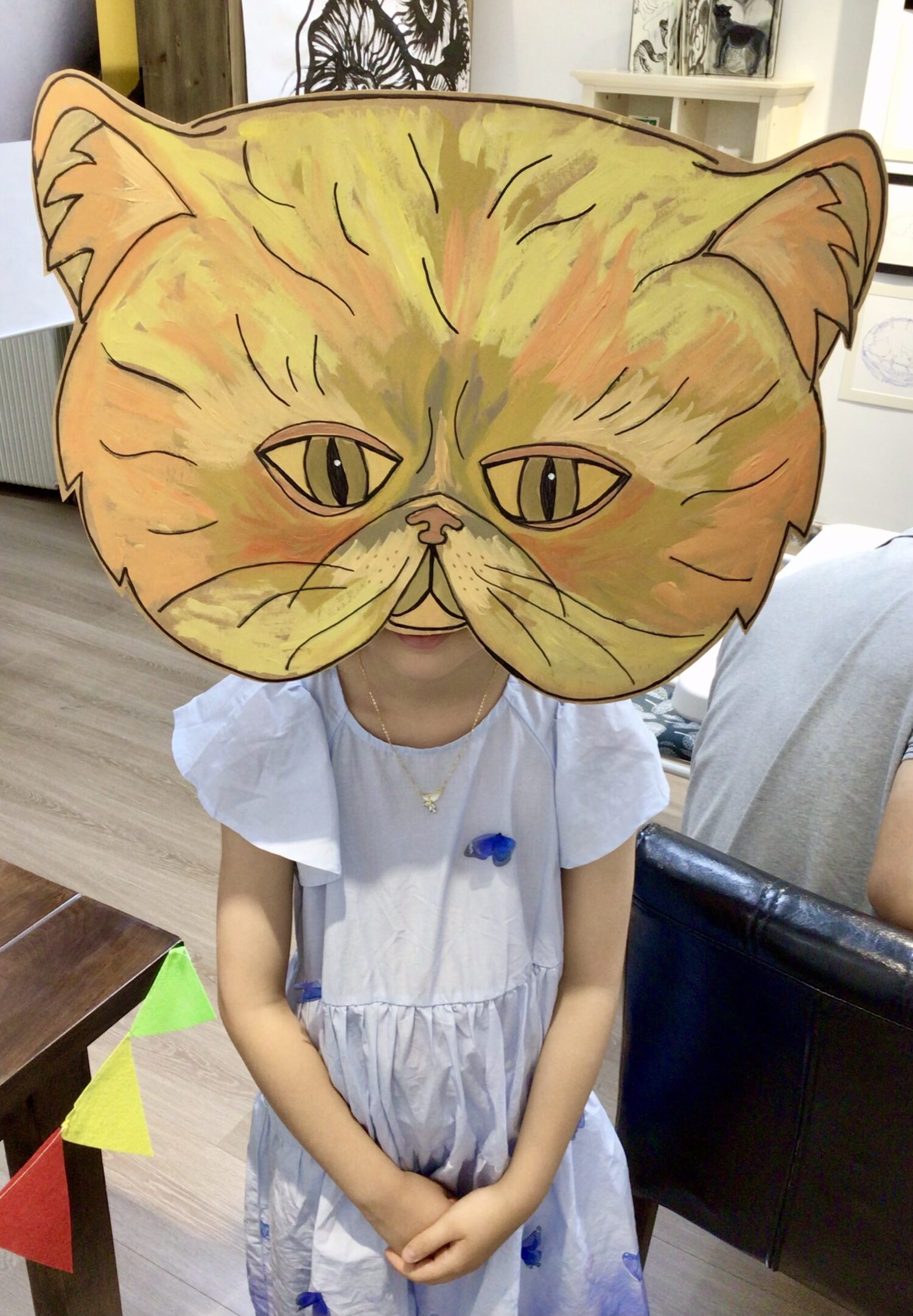

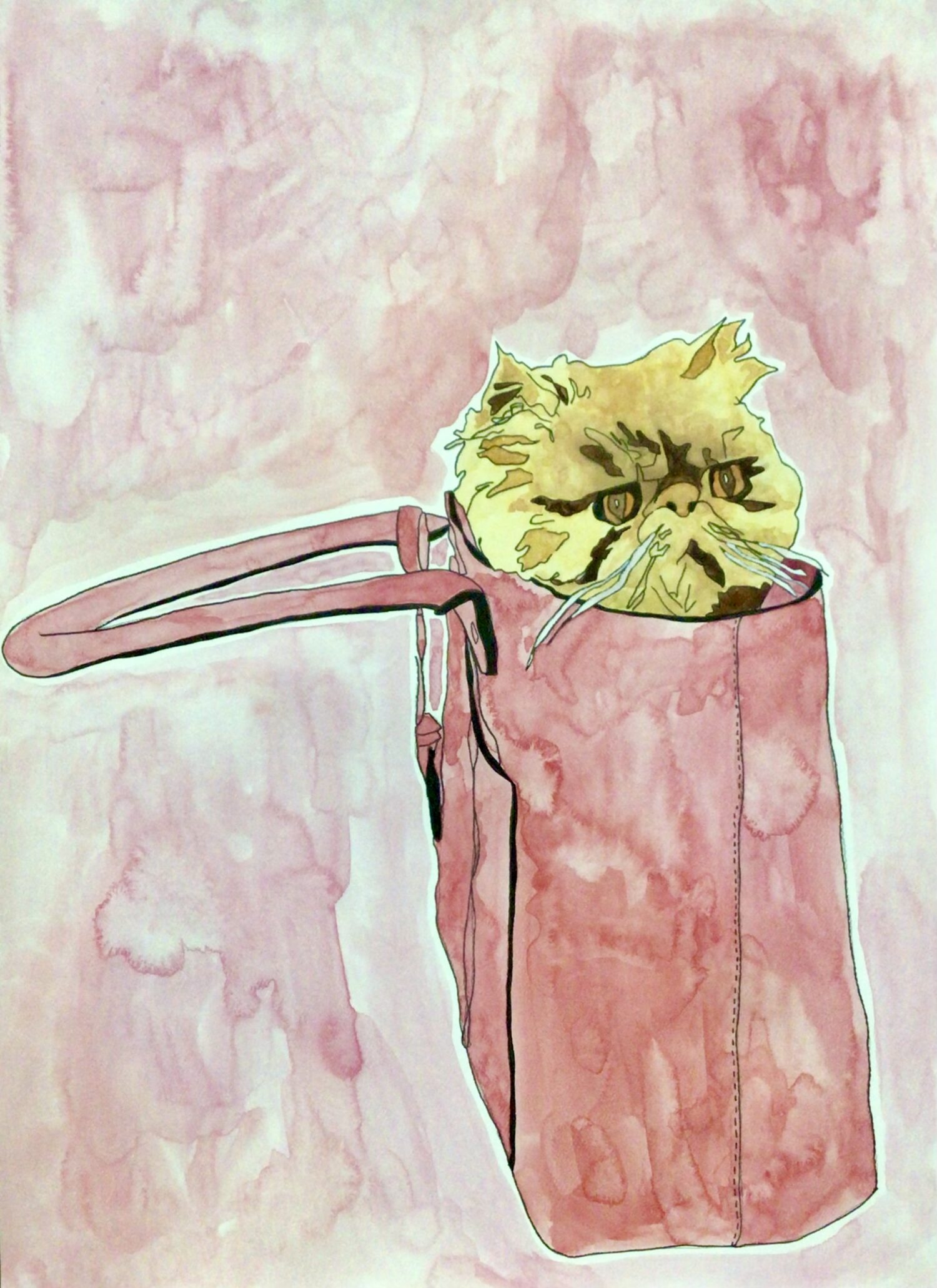

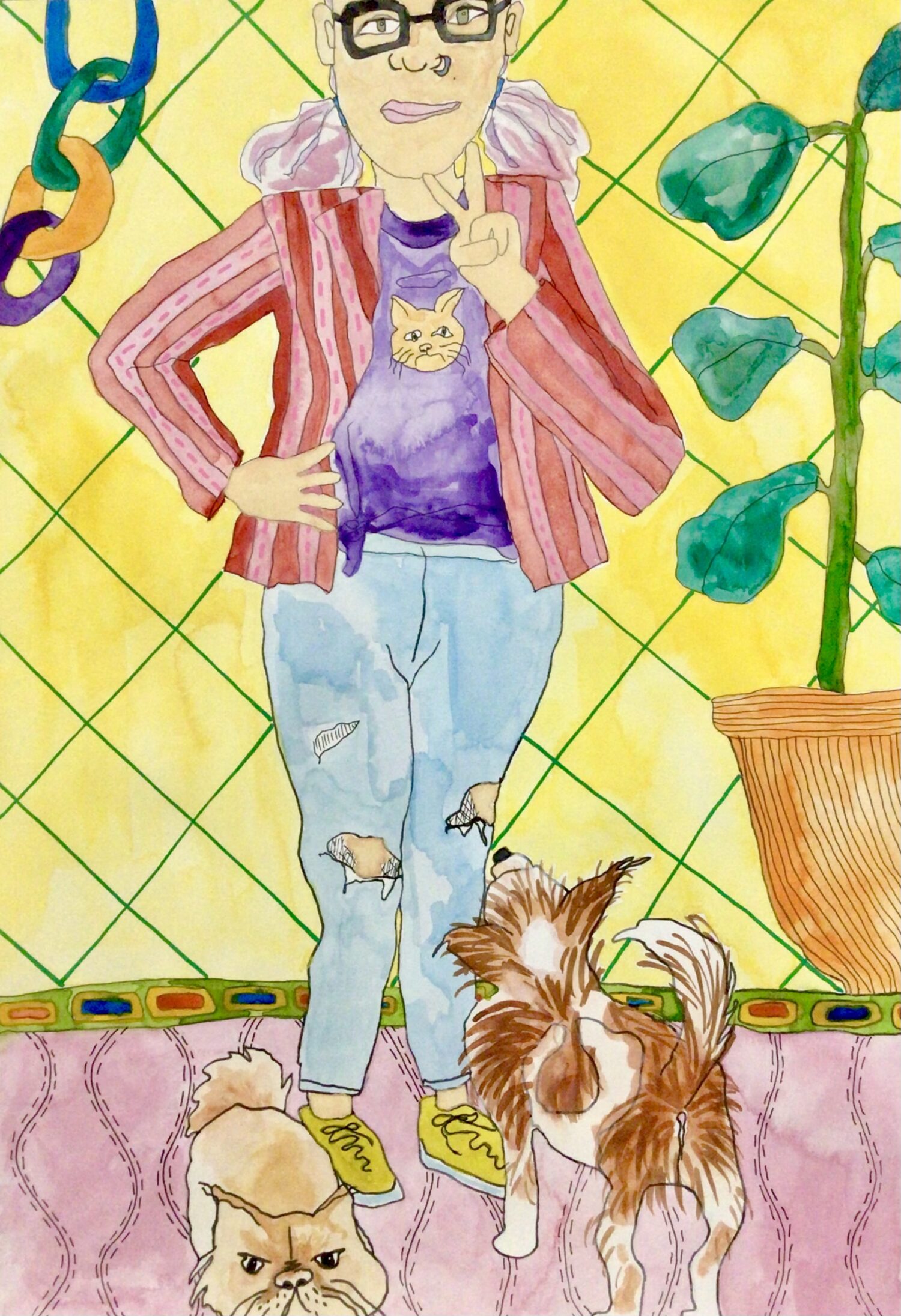

I had recently started experimenting with more illustrative work focused on my own pets, Rigby and Beanie. Inspired by Dallas-based artist Madaline Donahue—whose work explores the chaotic, tender intersection of motherhood and creative life—I had been making paintings that felt personal and immediate: crowded beds, Beanie’s dramatic flair, Rigby’s morning wake-up scratches to my face. It was funny and tender work—small moments elevated.

I told Hanna I could probably contribute five paintings and a few photographs. But once I got started, I couldn’t stop. The project snowballed into nearly 10 paintings and another 10 photographs. I even had prints and small books ready to go. Hanna was thrilled. We began planning our show together in earnest.

To my surprise, the watercolors came fast and furiously. I’m not a painter by default—I’m more installation, performance, video, and large-scale work. But there I was, night after night, painting the wild tufts of Beanie’s hair, the gleam in Rigby’s eye. It became something deeper than artmaking—it was healing. I was processing the sudden loss of Rigby and reflecting on what his presence had meant in my life. This was quieter work than I’m used to, but deeply cathartic and grounding.

The reception was packed—around 250 people wandered through over the course of the afternoon. The room buzzed with conversation, laughter, and memories. Though I haven’t painted since, that show made me realize something. For the past several years, I’ve been carrying a deep disappointment, a weight that made making art feel distant—like a place I once lived but could no longer return to. But this show reminded me that maybe art, like grief, comes in waves. It arrives unexpectedly, reshaping you as it moves through.

Enjoy the images below! And if you’d like to follow my journey as I transition to life and work in Africa, I’d love for you to sign up for my newsletter.